Imagine a world where a diabetes diagnosis was a death sentence. A world where parents watched helplessly as their children wasted away, losing weight, strength, and their very will to live. The only available treatment was a grueling starvation diet that might prolong life for a year or two, but always ended in death. The world desperately needed a miracle. That miracle arrived in the hot summer of 1921, in a modest University of Toronto laboratory, forever changing the course of medicine and offering hope to millions, as reported by toronto-future.com.

Teddy Ryder: The Boy Who Learned to Climb Trees Again

The story of five-year-old Teddy Ryder is perhaps the most vivid illustration of what the discovery of insulin meant. In the spring of 1922, as news of the “pancreatic extract” from Toronto was just beginning to spread, little Teddy weighed just over 11 kilograms (about 25 pounds). He had stopped playing and could barely take a few steps without help. His uncle, a doctor from New York, wrote to one of the discoverers, Dr. Frederick Banting, in desperation: “I fear that only a few months… is all that he can last.”

Banting found a way to help. On July 10, 1922, after an exhausting train journey to Toronto, Teddy received his first injection. The result was astonishing. By the fall, the boy had grown so much stronger that he was able to return home to a new life. A year later, six-year-old Teddy wrote to his saviour: “I wish you could come to see me. I am a fat boy now and I feel fine. I can climb trees.”

This little boy lived for another 71 years, becoming one of millions whose lives were saved by the discovery born in the heart of Canada.

An Idea That Struck in the Middle of the Night

One late evening, a young Canadian doctor named Frederick Banting was preparing a lecture for students and reading a medical article about the pancreas. He wasn’t a renowned scientist, but a general practitioner. The work stretched late into the night, and eventually, the exhausted doctor fell asleep. But even in his sleep, his mind seemed to continue searching for an answer. It happened on the night of October 31, 1920. Waking from a restless sleep, Banting suddenly sat up and, in the darkness, jotted down the words that would forever change not only his life but the fate of millions with diabetes.

He scribbled a 25-word hypothesis in his notebook that became the starting point for what would, within the next year, become one of the greatest medical achievements of the 20th century. Banting theorized that trypsin, a substance produced in the pancreas, was destroying another one of its secretions—the one responsible for regulating sugar. If the trypsin production could be blocked, he reasoned, this other secretion could be isolated.

With no lab and no research experience, Banting approached Professor John Macleod of the University of Toronto, a world-renowned expert on diabetes. Macleod, though skeptical, agreed to give Banting lab space, an assistant, and test animals for the summer holiday.

And so, on May 17, 1921, Banting and his assistant, biochemistry student Charles Best (who reportedly got the position on a coin toss), began their experiments. The conditions were spartan. The lab was poorly equipped, and the summer heat made the work a true ordeal. Banting and Best worked tirelessly. The summer was filled with failures and grueling labour, but by August, their notes began to show the long-awaited results: the extract from the dogs’ pancreases was consistently lowering blood sugar levels. It was a breakthrough. They were on the right track.

The University of Toronto laboratory where insulin was discovered

From Extract to Medicine: The Decisive Step

Seeing the initial results, Macleod recognized the scale of the discovery and brought his entire team onto the project. The next critical task was to purify the extract so it could be safely administered to humans. This work was led by biochemist James Collip. It was his expertise and persistence that transformed the crude extract from calves’ pancreases into a pure, stable preparation they named insulin.

On January 23, 1922, the moment of truth arrived. At Toronto General Hospital, 14-year-old Leonard Thompson, weighing only 29 kilograms (about 64 pounds) and near death from diabetes, was given the first injection. This initial attempt caused an allergic reaction due to impurities. But 12 days later, after being treated with Collip’s refined preparation, a miracle occurred. The boy’s blood sugar normalized. He began to gain weight and return to life.

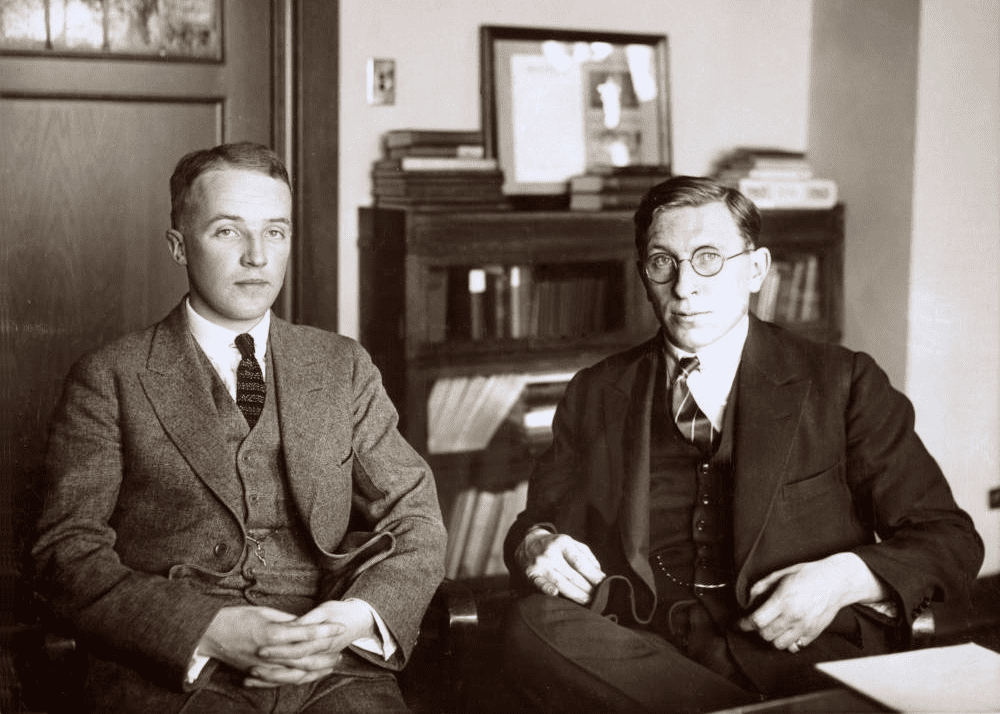

Frederick Banting and Charles Best

News of the cure spread like wildfire. Patients began flocking to Toronto from all corners of the globe. Dr. Bill Bigelow, a young surgeon who witnessed the first trials, recalled how patients in diabetic comas would “sharply awaken, literally snatched from the brink of death.”

Toronto: The Global Centre of the Fight Against Diabetes

The discovery of insulin turned the world’s attention to Toronto, transforming the city into a vanguard of medical research. The success was so profound that production of the treatment needed to be scaled up urgently. The university’s Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories began ramping up production, and the university soon entered into an agreement with the American pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly & Co.

In 1923, Frederick Banting and John Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine. Banting, outraged that his assistant Best was not included, immediately shared his prize money with him. In response, Macleod shared his portion with Collip, recognizing his crucial role. Interestingly, Frederick Banting became the youngest-ever Nobel laureate in Medicine.

But the noblest step of all was selling the patent for insulin to the University of Toronto for a symbolic $1. The discoverers gave up potential millions to ensure the medicine would be accessible to all who needed it.

A Century Later: Legacy and Future

Today, a century after that historic summer, insulin continues to save and improve the lives of an estimated 150 million people worldwide. However, as modern doctors note, insulin is not a cure for diabetes, but a treatment to manage it.

Dr. Alice Cheng, an endocrinologist at the University of Toronto, says it places a huge mental burden on the individual and their family. She adds that trying to keep blood sugar levels in a normal range can feel like “walking a tightrope.”

The legacy of Banting, Best, Collip, and Macleod lives on in the culture of innovation that still thrives in Toronto. The university and its partner hospitals remain at the forefront of biomedical science, and Canadian researchers across the country are working tirelessly to finish the job they started: to find a definitive cure for diabetes.

The discovery of insulin is not just a story of a scientific breakthrough. It is a story of human persistence, teamwork, and incredible altruism. It forever etched the University of Toronto into medical history and became one of the brightest symbols of the city’s innovative spirit, proving that ideas born here can save lives around the world.