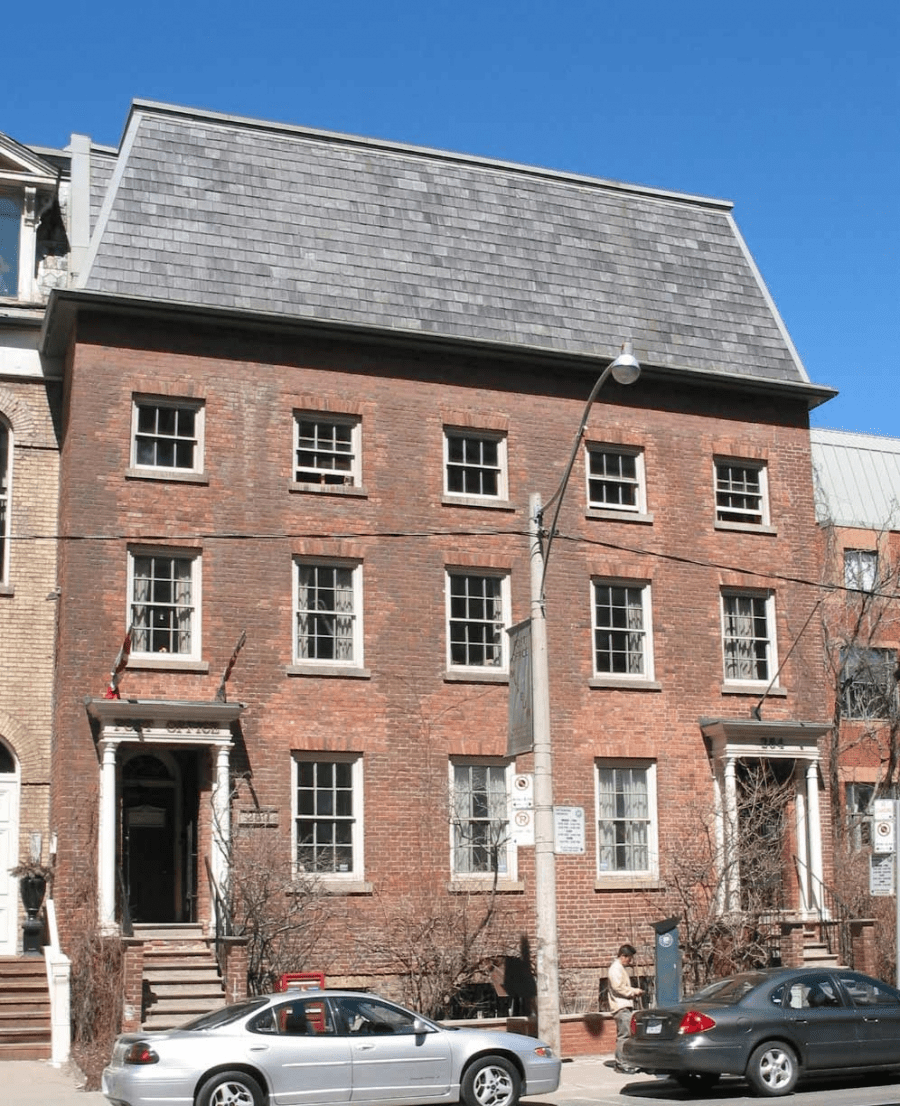

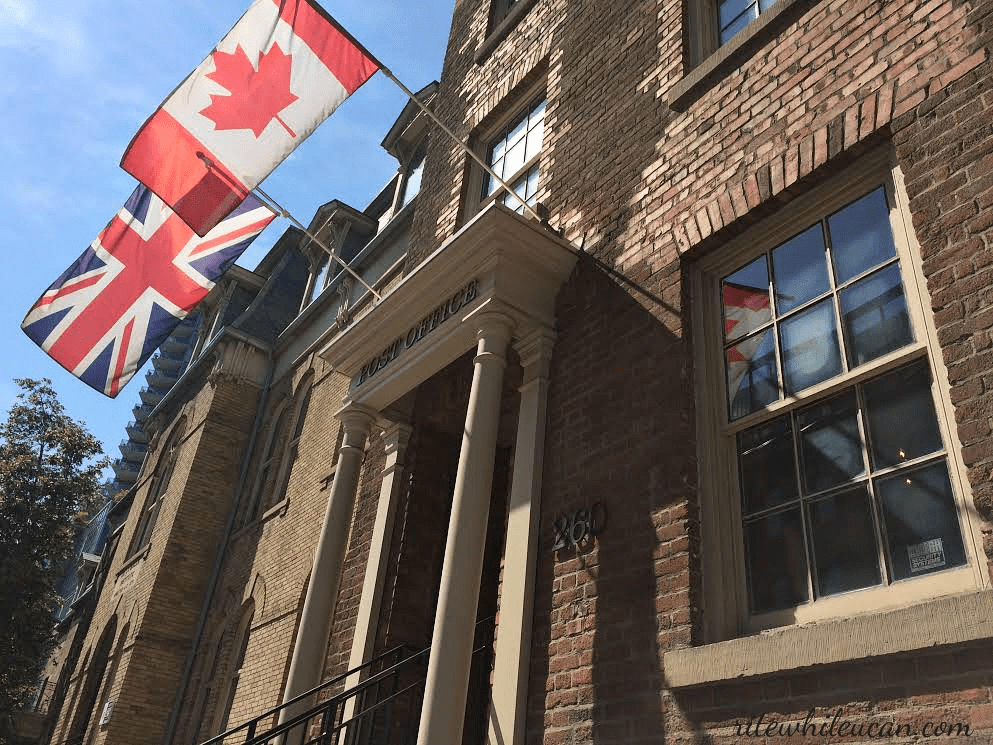

Toronto’s First Post Office is a small, meticulously restored building located across from George Brown College, near Adelaide Street. Built in 1833 in the Georgian style, the post office doesn’t draw much attention to itself. The post office itself operated until 1839. Read more at toronto-future.

Background to the Creation of an Official Post Office

In its early days, York was little more than a muddy patch of land on the shores of Lake Ontario. It was a predominantly rural settlement—small, provincial, and, according to visitors, extremely backward. Only after the War of 1812 did York begin to transform into a bustling town, and over the next decade, new wharves, warehouses, and commercial enterprises appeared. By the 1830s, the existing system of governance proved incapable of handling the new demands. York, as the provincial capital, was becoming a commercial hub, and with this growth came demands for better roads, sanitation, and other services befitting a capital city. The old system, designed for small villages, was no longer adequate for the new realities. In 1834, the provincial government decided to incorporate the City of Toronto.

Before this, York had four post offices. But it was the building on Adelaide Street that became Toronto’s first official post office.

James Scott Howard – Toronto’s First Postmaster

Howard was born on September 2, 1798, in County Cork, Ireland. He arrived in Canada in 1819, first settling in New Brunswick before moving to York. He was appointed to work in the post office under the supervision of York’s postmaster, William Allan. In July 1828, Howard was promoted and became the postmaster. Everything went well for several years. The Adelaide Street building had two storeys: the Howard family lived on the upper floor, while the post office operated on the lower. When Toronto officially gained city status, James Scott Howard went down in history as its first postmaster.

It’s hard to imagine just how important the post office was in the 1800s. The office became a huge hub of activity, as it was located near the financial district and the harbour, and it was vitally important for people awaiting news from relatives in their homelands. Postmasters would publish quarterly announcements in the newspapers, listing those whose letters had arrived. Queues became a common sight. The post office also had a room where people would gather to have their letters read to them. It’s worth noting that this was a time when basic literacy was not yet the norm due to the lack of a public education system. For this reason, postal workers were prepared not only to read letters but, in some cases, to help write replies.

By the 1830s, the authority of the ruling elites began to be challenged. The harder they tried to maintain control, the more discontent grew. The times were changing, whether they liked it or not. In 1837, the situation reached a boiling point—an armed rebellion against the government began. Rebellions took place in both Upper and Lower Canada. They were all suppressed within a year, and the situation, at first glance, returned to the status quo. However, the victory over the rebels was the last gasp for the ruling elite. Although the rebels were subdued, in the long run, they were the ones who won. Within a decade, the Durham Report was produced, which outlined plans for responsible government and laid the groundwork for the eventual collapse of the “Family Compact”.

James Scott Howard was not part of the “Family Compact”—for starters, he was not an Anglican and did not belong to the ruling families. Secondly, he had a reputation as a fair man. He had friends from all walks of life, including some who were key players in the rebellion. Howard maintained political neutrality and, by all accounts, stayed out of politics. However, he was inadvertently drawn into the Rebellion of 1837, unjustly accused of supporting the rebels. The Ontario government dismissed him without any formal charges or evidence. The “Family Compact” considered his friendship with some of the rebels as proof of his guilt. And that is how he lost his position. The position of postmaster was given to Albert Berczy, who lived in the building for about a year. In 1839, the post office was moved from Adelaide Street to Front Street (just west of Yonge Street), at which point the Adelaide building ceased to function as a post office.

The Building’s Subsequent Fate

After the post office moved, the building was rented out. In 1873, Howard sold it. Over the next 100 years, the property changed hands numerous times, so it’s not surprising that it became an unrecognizable ruin—Toronto has not always been careful with its history. Only after a fire in 1978 nearly destroyed this historic landmark did the city’s residents finally begin to recognize its importance. The building was purchased, restored, and returned to its simple, authentic beauty. For a time, it once again became a local post office.

The Post Office is Now a Famous Toronto Museum

The post office on Adelaide now serves as a museum. The main hall is a fully functioning post office, which even features replicas of the original post boxes. You can wander through the other rooms, look at the exhibits, try writing with a quill pen (it’s harder than it looks), and learn more about the building’s history. Upon request, letters sent from this office can be stamped with a replica of the red postmark from that era.