Toronto, like many other Canadian cities, is situated on a large body of water. For centuries, water has often been at the intersection of transportation routes, making oceans, lakes, and rivers vital corridors. More at toronto-future.

Toronto’s location on Lake Ontario, the first of the Great Lakes when travelling from the St. Lawrence River, has been crucial to the city’s history. Long before the arrival of Europeans, this area was home to Indigenous peoples who used the site as the start of a shortcut from the lower Great Lakes to the upper ones.

Trading Camps. Control of Lake Ontario After the American Revolution

The French knew about the route through Toronto as early as the 1600s and periodically set up trading camps in the area. However, it wasn’t until the 1720s that they established a permanent post in Toronto. In 1720, the French built a small trading post on the Humber River at the southern end of this route. In 1750, they began construction of Fort Rouillé—a small trading post on the shore of Lake Ontario, slightly east of the Humber.

After the American Revolution, Toronto became a key centre for the fur trade and for attracting new settlers. The British, concerned about threats from the United States, decided this city would be the ideal location for a naval base. Governor John Graves Simcoe believed that the area’s protected harbour would allow his forces to control Lake Ontario, and the Toronto Passage would ensure movement and supply to the upper lakes if the Americans gained control of Lake Erie. The construction of Fort York began in 1793, a time now considered the beginning of urbanized Toronto.

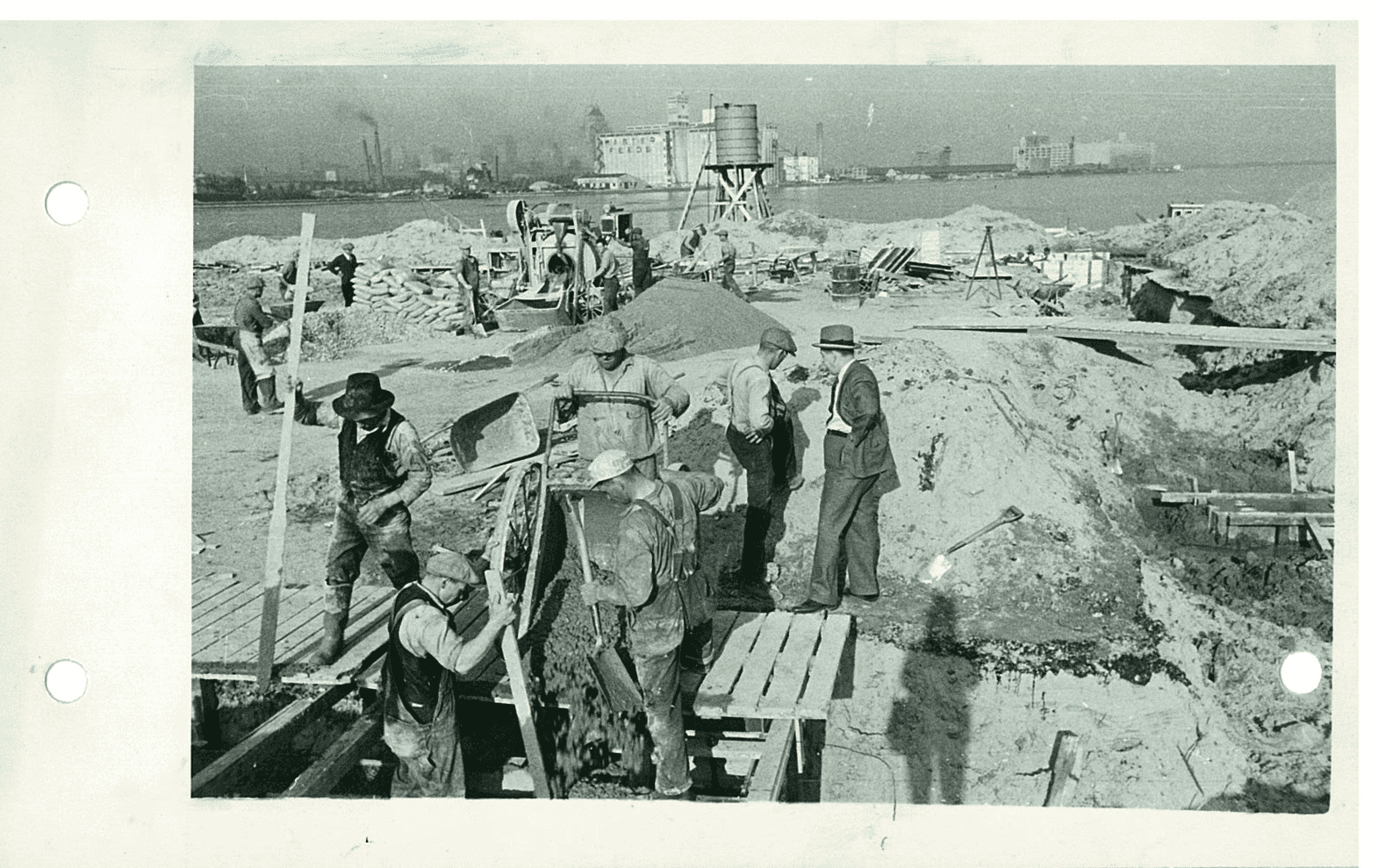

Expanding the Shoreline

Since much of the city’s primary trade was conducted by water, locating manufacturing facilities near the waterfront was a strategic advantage. Factories on the lakefront allowed for the easy receipt of raw materials and the efficient transport of finished products. However, in the 1830s and 1840s, the lack of available land along the waterfront severely limited the development of shipping, industrial, and railway infrastructure. In the 1850s, a massive landfill campaign was undertaken to extend the shoreline south to the Esplanade. Over the next hundred years, the shore continued to be extended further south. The original shoreline was located north of the modern railway corridor, and Front Street was built along the edge of this line. Landfilling continued until the 1950s.

The Mass Move to the Suburbs and the Urban Revolution

Much changed after the Second World War: the concentration of industry along the waterfront made the city centre unappealing for residents. For decades, affluent Toronto residents had been moving from industrial areas to cleaner suburbs, and when cars became affordable for most people, residents began leaving the city centre in droves. However, since many jobs remained in the central industrial districts, the need arose for major roads and highways to provide convenience and comfort for the community. At that time, highways were typically built in rings around cities. For most communities located on the water, part of this ring ran along or near the waterfront. Toronto was no exception: in the 1950s, the Gardiner Expressway was built, effectively cutting the city’s residents off from the lake.

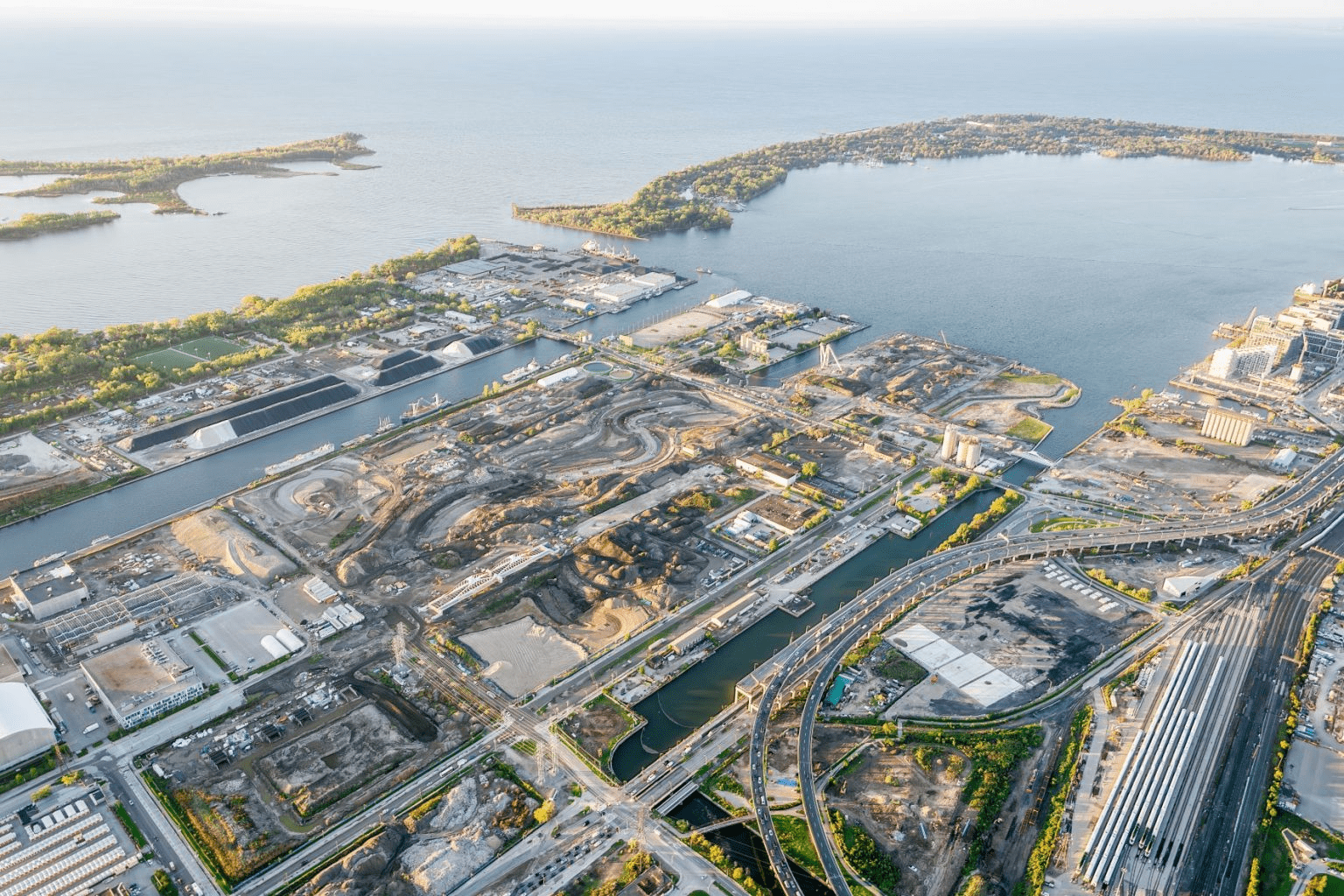

In the 1970s, a kind of urban revolution was taking place worldwide, and cities began to rediscover their waterfronts. Major cities not only renewed these areas but also used redevelopment projects to make a statement on the international stage. In general, revitalized waterfronts attracted new residents, employers, jobs, and tourists. Toronto was one of the last major waterfront cities to take on the revitalization of its shoreline. For many years, there were numerous ideas about what to do with Toronto’s waterfront, but it lacked a single, unique vision. Harbourfront Centre, Queens Quay Terminal, and the surrounding area were the results of an attempt to renew the central waterfront in the early 1970s.

Working on Waterfront Revitalization

In 1999, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, Ontario Premier Mike Harris, and Mayor Mel Lastman announced the creation of a task force to develop a business plan and recommendations for waterfront development as part of Toronto’s bid for the 2008 Summer Olympics. The task force was chaired by businessman Robert Fung. The group concluded that revitalizing the waterfront was essential, as it represented “an almost unprecedented development opportunity” that would have a “significant positive economic impact on the city, the region, and the country.” The task force stressed that waterfront renewal was not just a massive public project, but an integrated partial solution to the environmental, transportation, infrastructure, housing, economic, and tourism challenges facing the city. It was also noted that the need and economic viability of renewing Toronto’s waterfront were so clear that this process should proceed regardless of the Olympic bid. After Beijing was awarded the 2008 Olympics, the three levels of government reaffirmed their support for the revitalization of Toronto’s waterfront.

In November 2001, the three levels of government created Waterfront Toronto (formerly known as the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation) to oversee all aspects of planning and development for Toronto’s central waterfront.

The corporation’s Board of Directors began its meetings in February 2002. In March, a small group of key staff was hired, and an office was established. In April, the corporation hired a program manager, the Toronto Waterfront Joint Venture, to oversee the implementation of waterfront projects. In December 2002, the Government of Ontario passed the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation Act, which gave the corporation the status of an organization responsible for planning and managing the revitalization process on an ongoing basis.

Strategy for Protecting Archaeological Heritage

Waterfront Toronto, in partnership with the City of Toronto, developed a comprehensive Archaeological Conservation and Management Strategy (ACMS). It aims to protect and interpret the waterfront’s archaeological heritage and to develop policies and protocols for managing these resources before the large-scale construction required for revitalization begins. The ACMS, developed with support from stakeholders and the public, has helped implement innovative policies for both Waterfront Toronto and the city as a whole. In addition to identifying areas where archaeological resources are likely to be found, the strategy also emphasizes the importance of honouring cultural heritage and understanding the past, including the evolution of the shoreline, Indigenous settlements, and the development of shipping, railways, and industrialization on the waterfront.