Toronto’s history is deeply intertwined with its railways. Beginning in the mid-19th century, they became the main artery for transporting goods and people, leading to the formation of a “union station” and an entire industrial zone around it. This established the city as a key economic hub, setting the pace for the development of the entire region. Railways continue to shape Toronto to this day. Although freight traffic no longer flows directly into the city centre, these transport arteries remain indispensable corridors for logistics and supporting local industry. Furthermore, rail transport is taking on an even greater role as a fast, space-efficient, and environmentally friendly way for city dwellers to travel. More on toronto-future.

However, there’s a downside: railway tracks stretch for kilometres, creating barriers that hinder pedestrian and cyclist movement, forcing them to take significant detours. Improving access across these corridors and developing parallel routes could significantly enhance the city’s active transportation network. Moreover, railways often dissect natural and recreational areas, further limiting access to open spaces and impacting the quality of the urban environment.

The Railway That Changed Toronto

The arrival of the railway in 1853 forever changed the lives of Torontonians, providing avenues for the active movement of goods, passengers, and innovative ideas. This marked the beginning of an economic and industrial boom: businesses gained new trade opportunities, tourists found a convenient way to discover the city, and new residents were welcomed to a promising future. The first railway to lay tracks into the city was the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway, but others soon competed for dominance in the region, including the Great Western Railway, Grand Trunk Railway (GTR), and Canadian Pacific (CP) Railway.

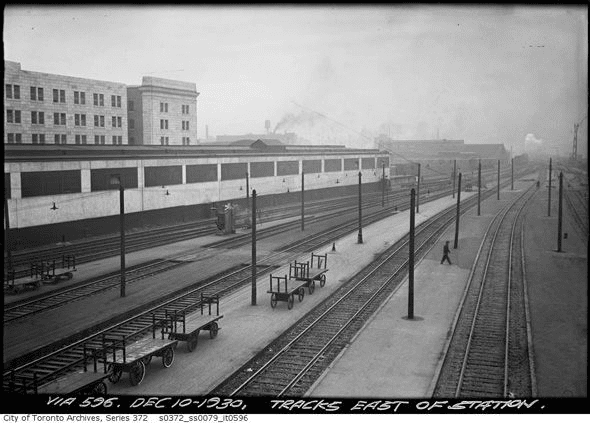

As railway traffic grew, it became clear that the city needed a central transfer hub. Thus, the idea of Union Station – a joint terminal for several companies – was born. The first station opened in 1858, followed by a second in 1873, but both quickly became inadequate for the burgeoning passenger volumes. In 1906, GTR and CP formed a joint company, the Toronto Terminals Railway (TTR), which undertook the construction of the third and current Union Station. The station building itself was erected by 1920, but the completion of all its infrastructure – tracks, train sheds, and underground passages – took another decade. During this period, the GTR faced a financial crisis and was nationalized, becoming part of the Canadian National (CN) Railway. Subsequent bankruptcies, mergers, and acquisitions led to all key railway lines in the city falling under the control of either CN or CP. Meanwhile, the TTR remained a joint company, and it continues to manage this vital railway hub to this day.

From the Railway Era to Modern Transportation

In the mid-20th century, the railway boom gave way to the automobile era, transforming Toronto’s transportation landscape. The city centre expanded, the Greater Toronto Area experienced rapid population growth, and industry shifted from heavy manufacturing to office and commercial sectors. Rising land values and business costs gradually pushed freight yards and depots to the outskirts. Meanwhile, the demand for fast and efficient passenger rail service only grew. However, passenger services were no longer as profitable for private railway companies, leading them to reduce routes or abandon them altogether. This compelled the government to intervene to preserve critical transportation corridors and ensure residents’ access to rail services.

In 1977, the federal government established VIA Rail, a Crown corporation that took over intercity passenger services from CN. The following year, it also assumed CP’s routes, creating the national passenger rail operator we know today. Even earlier, in 1967, GO Transit was launched as a temporary experiment – a commuter train system. But over time, the need for it only grew, and as freight traffic in the city centre diminished, GO Transit (along with its parent agency, Metrolinx) began purchasing railway lines. This allowed the regional carrier to gain more control over scheduling, operations, and route development. Today, CN’s freight operations are largely concentrated on the city’s outskirts, while CP (now Canadian Pacific Kansas City – CPKC) still maintains a corridor through the core. However, the once-extensive network of freight spurs has gradually disappeared: tracks to the Port Lands were removed in the early 2020s, and freight trains have not passed through Union Station for many years.

Meanwhile, GO Transit is often operating near its capacity limits. Since the early 2000s, a massive infrastructure expansion has been underway: adding second tracks on routes, creating space for express trains, and building new maintenance facilities. One of the largest projects was the Georgetown South Expansion, which added new tracks between Union Station and Pearson Airport, eliminated road crossings (grade separations), enabling the launch of the Union Pearson Express and increased GO Transit service frequency.

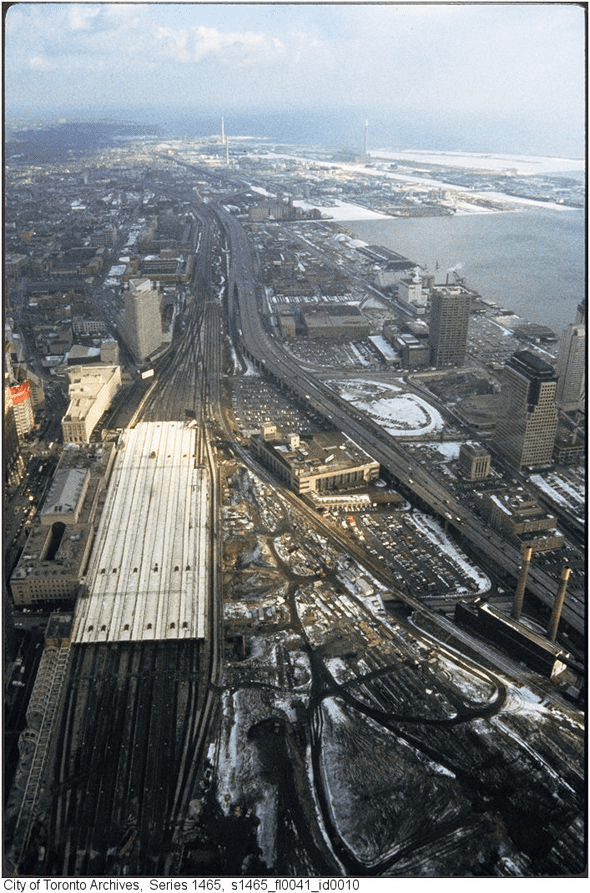

Union Station Rail Corridor: Toronto’s Transportation Artery

The Union Station Rail Corridor (USRC) is Toronto’s main transportation artery, consolidating numerous railway lines into a single flow around Union Station. It stretches from Strachan Avenue in the west to the Don River in the east, forming a key route for hundreds of thousands of passengers daily. The corridor includes two strategic GO Transit layover facilities: Don Yard near the Don River and North Bathurst Yard between Spadina Avenue and Bathurst Street. Here, trains are stored after the morning peak period, preparing for the evening commute.

The USRC was once part of vast railway yards and freight depots that occupied the lands south of Front Street. Over time, as CN and CP relocated their freight operations from this area, it was transformed into a new hub of urban life. The former Railway Lands are now home to some of Toronto’s most iconic landmarks. The most famous among them is the CN Tower, built by Canadian National as a symbol of Canada’s technological progress and industrial strength. Other notable sites include the Rogers Centre (formerly SkyDome), Scotiabank Arena, and the modern residential neighbourhoods of CityPlace and SouthCore.

Modernization of the USRC

Despite the loss of some railway lands, the USRC remains the heart of the city’s transportation system. It features 9 to 16 tracks with a total length of 40 km, 8 major sets of crossovers, 250 track switches, and 80 signals. Over 250,000 passengers pass through it daily, making Union Station the busiest transportation hub in Canada. Metrolinx acquired this corridor in 2000 to ensure its effective management. Despite limited space for expansion, extensive modernization work is ongoing: upgrading signaling systems, optimizing track layouts, and improving infrastructure to make the USRC an even more reliable and faster transportation corridor for the future.

The Oakville Subdivision connects to the USRC at Strachan Avenue and runs southwest along the lake to the city’s western boundary near Long Branch Station. This line was part of the original Lakeshore GO Transit line when operations began in 1967. The corridor initially belonged to CN and was acquired by Metrolinx in 2012.