Every year, as the summer heat descends on Toronto, turning the city into a sweltering concrete jungle, the skyscrapers of the Financial District, hospital operating rooms, and the Scotiabank Arena all remain pleasantly cool. This chill doesn’t come from thousands of humming rooftop air conditioners. Its source is hidden deep beneath the surface, at the bottom of Lake Ontario. It’s the Deep Lake Water Cooling (DLWC) system, one of the city’s most impressive and sustainable innovations—a true hidden giant working for the good of the metropolis.

This innovative system, developed by Enwave in partnership with the City of Toronto, is more than just a technological marvel. It’s a cornerstone of the city’s TransformTO strategy, which aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2040. As toronto-future.com reports, it serves as a powerful example of how urban infrastructure can work in harmony with nature to solve critical energy and environmental challenges simultaneously.

The Problem: A Big City’s Energy Appetite

Imagine the energy required to cool hundreds of skyscrapers in a major downtown core. Traditional air conditioning (AC) systems, or chillers, consume a colossal amount of electricity, placing an immense strain on the power grid, especially during peak heatwaves. These systems release tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, worsening the greenhouse effect, and rely on harmful chemical refrigerants. On top of that, the waste heat from these AC units is vented directly into the urban air, contributing to the “heat island” effect that makes the city even hotter. It was a vicious cycle that demanded an innovative solution—and Toronto found one.

An Ingenious Solution from Nature’s Depths

The initiative began in the late 1990s when Enwave and the City of Toronto identified a unique opportunity to use a sustainable resource right on their doorstep. At a depth of 83 metres in Lake Ontario, the water temperature remains a stable 4°C all year round. This cold water provides a vast, renewable resource for cooling.

The project, completed in 2004, was an ambitious $170-million (CAD) undertaking. It involved laying three massive 1.6-metre diameter high-density polyethylene (HDPE) intake pipes. Each pipe extends five kilometres from the shore out onto the lakebed. In total, 15,000 metres of pipe were welded and deployed.

How the System Works: A Symbiosis of Technology and Nature

Conceptually, the DLWC technology is surprisingly simple and elegant. It operates using a series of interconnected water loops that transfer heat energy, but the water from different loops never actually mixes.

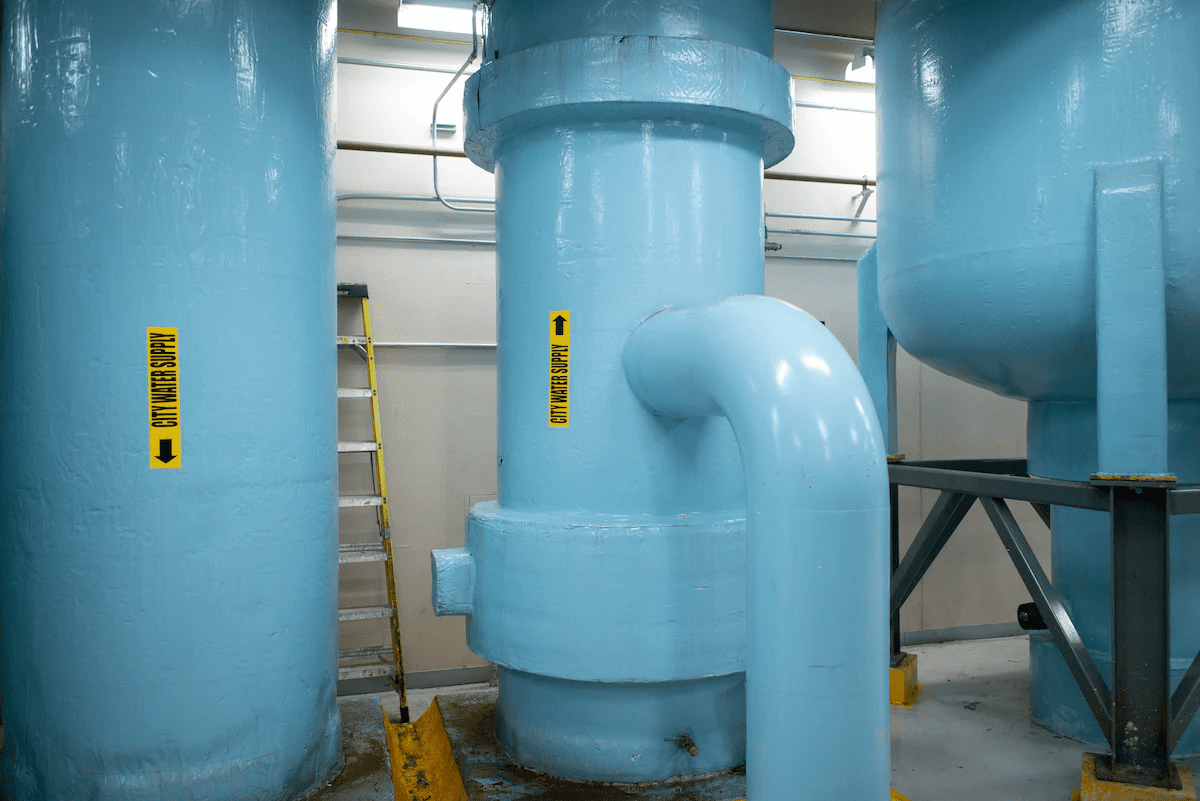

- Water Intake. Cold water is drawn from the lake depths through the intake pipes and first travels to a Toronto Water filtration plant. This is where a unique symbiosis occurs: the water destined for cooling is the very same water used for the city’s drinking water supply. It is treated and purified to meet safe drinking water standards.

- Heat Exchange. The purified cold water is sent to a pumping station, which houses 36 large plate-and-frame heat exchangers. This is where the magic happens: the cold lake water (in its own loop) absorbs heat from a separate, closed urban loop that circulates through downtown buildings. The lake water warms up slightly, while the water in the urban loop is chilled to about 4-5°C.

- Cooling the Buildings. This chilled water from the urban loop is then distributed through a 40-kilometre network of underground pipes to participating buildings. In each building, another set of heat exchangers transfers the “cold” to the building’s internal HVAC system. This water then circulates through fan coil units, cooling the air inside.

- Completing the Cycle. The now-warm water from the buildings returns to the central station to be chilled again. Meanwhile, the lake water that has done its job (and warmed up slightly) is sent into the city’s drinking water supply. This is an ingenious part of the design, as the city would have had to pump this water for distribution anyway. Any unused portion of the lake water is returned to the lake at a temperature close to its original state.

This creates a continuous cycle where the only major energy input is the natural cold from the lake, providing the city with a sustainable and incredibly efficient alternative to conventional air conditioning.

Scale, Efficiency, and Impressive Results

Since launching in 2004 with just a handful of clients, the DLWC system has grown into an energy giant. Today, it serves approximately 200 buildings, covering over 40 million square feet of real estate in downtown Toronto. Its clients include Financial District skyscrapers, eight hospitals, City Hall, hotels like the Fairmont Royal York, and even Steam Whistle Brewing.

The system’s benefits are staggering:

- The DLWC cuts electricity consumption for cooling by up to 90% compared to conventional systems. This results in annual savings of about 90,000 megawatt-hours—enough to power a town of 25,000 people. Scotiabank Arena alone saves an estimated 3 million kilowatt-hours annually.

- These savings translate to a reduction of 79,000 tonnes in carbon dioxide emissions annually. That’s the equivalent of taking 15,000 cars off the road. The system has also eliminated the need for ozone-depleting refrigerants.

- Because the system isn’t reliant on the power grid during peak summer demand, it is exceptionally reliable. This is critical for its clients, which include not just office towers but also major hospitals (like Toronto General and Princess Margaret), data centres, Toronto City Hall, and sports arenas. Furthermore, the system frees up valuable real estate that was once occupied by bulky chillers and provides more predictable energy costs.

Challenges and Global Potential

Despite its success, DLWC technology has limitations. It requires a specific set of geographic conditions: a deep, cold body of water located close to a high-density area of consumers. The massive upfront capital investment is also a significant barrier.

There are potential environmental considerations as well. Experts note that discharging warmer water near the lake’s surface could potentially trigger algal blooms. However, Toronto’s system addresses this by discharging the water deep into the lake using diffusers. Furthermore, while the system does use electricity to run its pumps, it draws power from Ontario’s low-carbon energy grid, which minimizes its overall carbon footprint.

Toronto’s DLWC system, along with similar seawater air conditioning (SWAC) systems in places like Hong Kong and the Bahamas, proves that innovative, large-scale sustainable projects are achievable. Carlyle Coutinho, President of Enwave, often wonders why the system doesn’t get more global attention.

Today, Enwave continues to expand its network, connecting new buildings and proving that the future of cities doesn’t lie in consuming ever-increasing amounts of energy, but in the intelligent use of the resources nature provides. The story of the DLWC is a powerful reminder that the most impactful innovations are often right under our feet—or in Toronto’s case, at the bottom of the lake.